Chinese Prefixes and Suffixes

As you progress to fluency, you’ll want to begin building up your vocabulary and learning more advanced terms in Chinese, such as the various ideologies, academic disciplines, and professions. The good news is that if you already know how to say “science” in Chinese, it’s pretty straightforward to create the terms for “scientist” or “scientific.” All you need to do is attach a prefix or suffix.

Since Mandarin Chinese has no alphabet, prefixes and suffixes take the form of additional characters affixed to the front or end of a word. For example, they are the -ology in “theology,” the -istry in “chemistry,” and the re- in “repeat“ or “rebuild.” Knowing a few prefixes and suffixes is a great way to learn more Chinese vocabulary without grinding your way through long lists of characters.

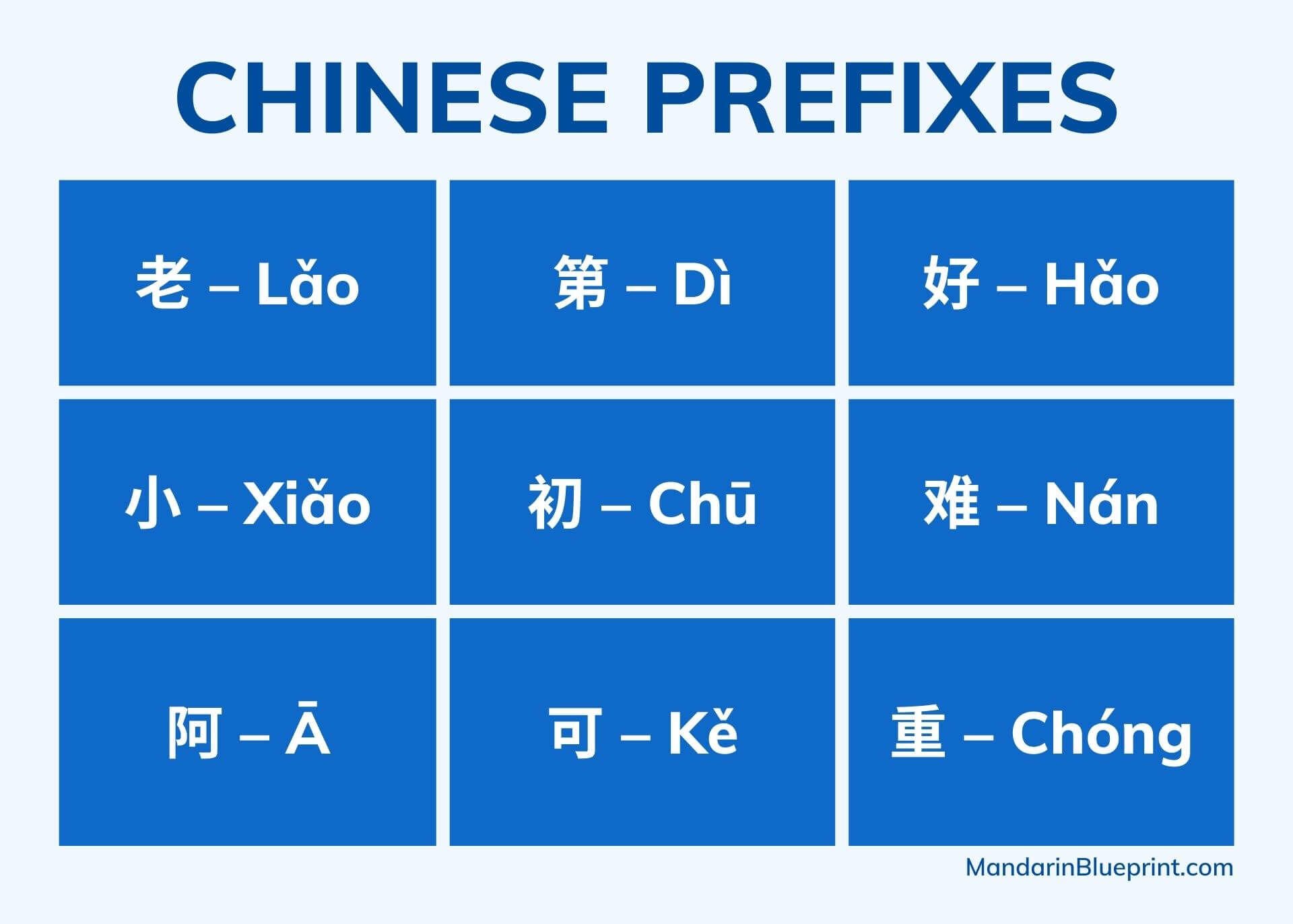

Chinese Prefixes

Prefixes in Chinese appear as additional characters affixed to the front of a word. Many Mandarin prefixes are special markers or honorifics used to describe family relationships. Some prefixes turn numbers into ordinals, while others distinguish between homonyms or make Chinese words easier to pronounce.

Most Mandarin prefixes have no direct equivalent in English, but the grammatical structure is straightforward. For example, learning the following prefixes will help you turn numbers into sequences, translate words for qualities and properties, and mark the difference between “start” and “restart,” “build” and “rebuild,” and so on.

老 – Lǎo

The ancient form of the Chinese character 老 was a picture of an older person hunched over and walking with the aid of a stick. The primary meaning of 老 lǎo is “old” (as in the opposite of “young.”)

When used as a prefix, 老 no longer means “old;” instead, it’s a term of respect. For example, you may have heard of the Dao De Jing (“Tao Te Ching”), the ancient Chinese wisdom text. The author is known as 老子 Lǎo Zǐ in China, which we frequently translate as Lao Tzu in the West.

Place 老 in front of a family name to form a respectful term of address for men you are familiar with. It’s difficult to translate into English but is often rendered as “Brother,” as in 老王 Lǎo Wáng (“Brother Wang”) or 老陈 Lǎo Chén (“Brother Chen”).

Sometimes, the 老 prefix is used as a term of respect in Chinese words like 老师 lǎoshī (“teacher”) and 老板 lǎobǎn (“boss”). Husbands and wives also refer to each other as 老公 lǎogōng (“husband”) and 老婆 lǎopó (“wife”), where 老 suggests intimacy or pleasant feeling.

Finally, you’ll find 老 in words for some animals, including 老虎 lǎohǔ (“tiger”), 老鹰 lǎoyīng (“eagle”), and 老鼠 lǎoshǔ (“mouse”). Here, the prefix carries no meaning but is used to help separate the word from other homonyms.

小 – Xiǎo

As an adjective, 小 means “little” or “young.” In China, it’s often combined with a family name to create nicknames for both men and women, generally for those younger than you are. Again, prefixes such as 小 have no proper equivalent in English, but you might translate 小李 Xiǎo Lǐ as “little Li” or “Miss Li,” depending on the context and relationship.

When added to a family name, 小姐 Xiǎojie means “lady” or “miss,” as in the phrase 张小姐 Zhǎng Xiǎojie (“Miss Zhang”). However, use this word with caution, as in some regions of China, 小姐 is slang for “prostitute.”

小 also functions as a meaningless prefix in Chinese words such as 小心 xiǎoxin (“careful,” “take care”), 小说 xiǎoshuō (“novel”), and 小偷 xiǎotōu (“thief”).

阿 – Ā

The Chinese prefix, 阿, is attached to characters for pet names, kinship terms, and family names, much like 小. The only difference between the two suffixes is that you use 小 to refer to those who are younger and 阿 to refer to your elders and seniors. Examples include 阿爸 ābà (“dad,” “daddy”) and 阿姨 āyí (“auntie,” “nursemaid”).

You can also use 阿 in the same way as 老 to denote the order of seniority within the family, as in 阿大 ā dà (“eldest child”) and 阿三 āsān (“third son or daughter”).

第 – Dì

Use the Chinese prefix 第 to rank things in a sequence and to turn numbers into ordinals: 第一 dì yī (“first”), 第二 dì èr (“second”), 第三 dì sān (“third”), and so on.

You can also use 弟 in combination with a measure word in phrases such as 第一个 dì yī gè (“the first one“), 第三次 dì sān cì (“the third time“), or 第四张 dì sì zhāng (“Chapter Four”).

初 – Chū

The original meaning of 初 chū was “beginning” or “early part of,” as in 夏初 xiàchū (“early summer”) or 十九世纪初 shíjiǔ shìjì chū (“the beginning of the 19th century”). You’ll most often hear it in 初中 chūzhōng, an abbreviation for 初级中学 chūjízhōngxué (“junior middle school”)

While both the 第 dì and 初 chū prefixes are used to rank things in sequence, 初 is far less versatile. As a prefix, 初 is used mainly to mark the days of the lunar year, such as 正月初一 Zhēngyuè chūyī, which is New Year’s Day (on the Chinese lunar calendar).

初 also describes years in middle school, so 初一 chūyī means “first-year,” 初二 chū’èr means “second-year,” and so on.

可 – Kě

可 means “can” or “able to,” as in 可以 kěyǐ (“can”).

Combine this versatile prefix with verbs to form new adjectives like you use the English suffixes “-able” and “-ible.” The only difference is that, in Chinese, 可 is a prefix rather than a suffix.

Examples include 爱 kěài (“cute,” “adorable”), 可靠 kěkào (“reliable”), and 可笑 kěxiào (“ridiculous,” “laughable.”)

好 – Hǎo

好 preserves its original meaning (“good”) when used as a prefix to form adjectives from verbs, in Chinese words such as 好看 hǎokàn (“good-looking”), 好吃 hǎochī (“tasty”), 好玩 hǎowán (“fun), and 好香 hǎoxiāng (“fragrant”).

In some cases, the meaning is closer to “easy” than “good,” as in the phrase 好用 hǎoyòng (“easy-to-use” or “convenient”).

难 – Nán

The prefixes 好 and 难 carry opposite meanings but are used similarly. When added before a verb, 难 means “difficult” or “bad.” Examples include 难 nánkàn (“ugly”), 难用 nányòng (“difficult-to-use”), and 难受 nánshòu (“uncomfortable,” “difficult to endure”).

Some of the Chinese words have no corresponding adjective in English. 难听 nántīng, for example, would have to be rendered as “bad” or “terrible,” as in 这首歌真难听 Zhè shǒu gē zhēn nántīng (“This song is terrible”).

重 – Chóng

重 means “to repeat” or “to duplicate.” When attached to other Chinese characters, 重 functions like “re-” in English, acting as the prefixes in terms like 重复chóngfù (“repeat”), 重建 chóngjiàn (“rebuild”), and 重启 chóngqǐ (“restart”).

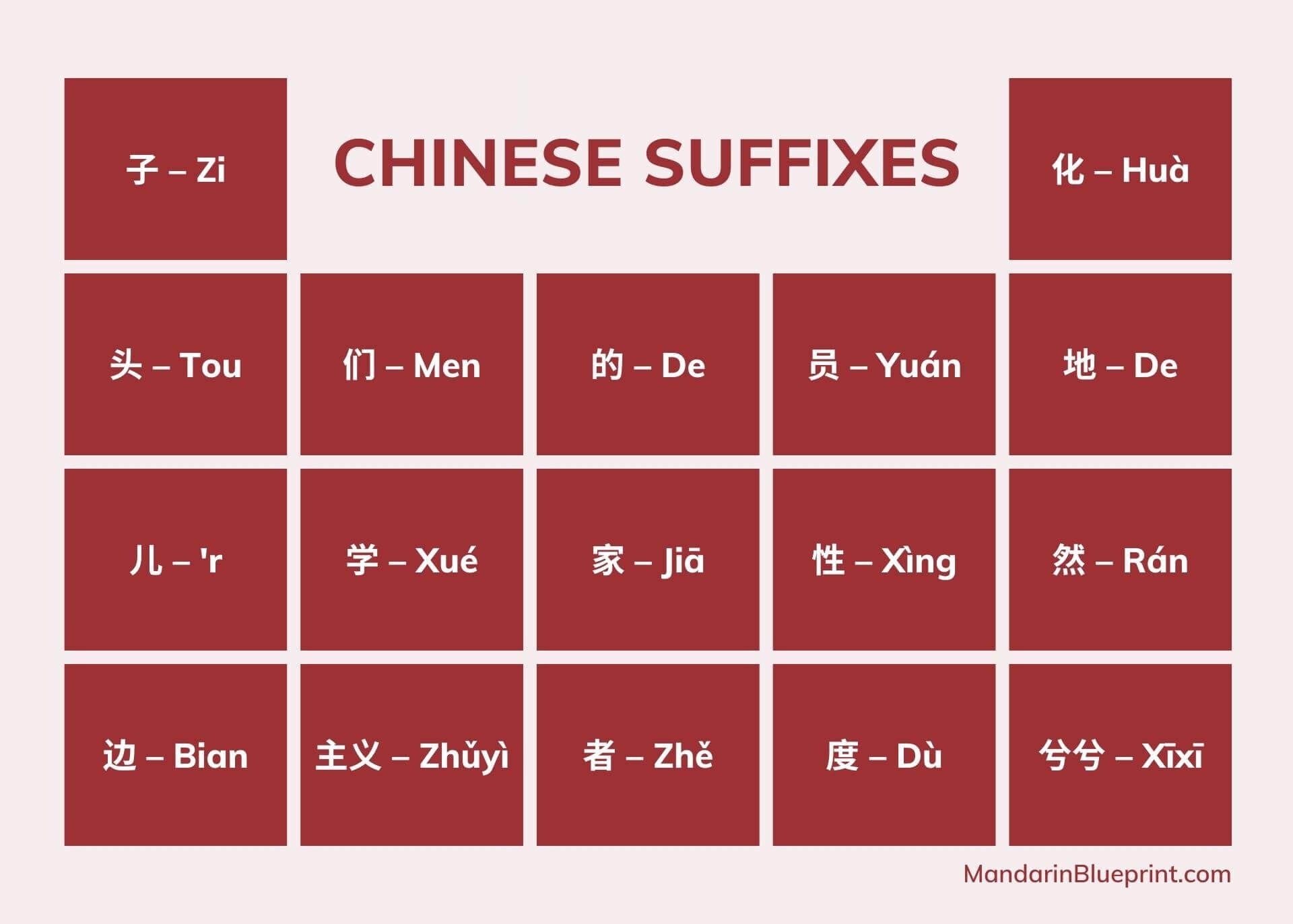

Chinese Suffixes

Although most Chinese suffixes are words in their own right, some are bound morphemes, which have meaning only in combination with other characters. Aside from forming many of our -ists and -isms, suffixes are the special markers used to complete a partial noun, distinguish between homonyms, or convert an adjective or verb into a noun.

Suffixes are much more widely used than prefixes in Chinese, and you are likely to have come across the majority of them already. These handy characters have a wide range of functions in Mandarin: use them to convert adjectives into adverbs, describe properties and qualities, and form the terms for various ideologies, academic disciplines, and generic job titles.

子 – Zi

The Chinese use 子 zǐ as an honorific to show respect to ancient philosophers and sages, including 老子 Lǎo Zǐ (Lao Tzu), 孔子 Kǒng Zǐ (Confucius), and 孙子 Sūn Zǐ (Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War).

In modern Chinese, 子 zi (pronounced with a neutral tone) is the most widely used of the nominal suffixes, providing the second syllable in many everyday Chinese words, such as 房子 fángzi (“house”), 袜子 wàzi (“socks”), and 猴子 hóuzi (“monkey”).

You can affix 子 to certain verbs to create a new noun, like the –er in “computer” or “cooker.” The primary meaning of the verb 夹 jiā is “to press” or “to pinch,” while 夹子 jiāzi is a noun meaning “peg” or “clip.” The verb 骗 piàn means “to cheat” or “to swindle,” and a 骗子 piànzi is, you guessed it, a “cheater” or “swindler.”

In everyday use, 子 converts adjectives into nouns, in which case it is usually pejorative. Examples include 傻子 shǎzi (“idiot”), 秃子 tūzi (“baldy”), and 胖子 pàngzi (“fatty”). Reserve these for use among close friends with a sense of humor!

头 – Tou

The Chinese character 头 tóu (second tone) means “head.”

As a nominal suffix, 头 tou (neutral tone) functions much the same way as 子 zi, turning a partial noun into a complete noun. Although 子 is the more familiar of the two suffixes, you’ll still hear 头 tou in many everyday Chinese words. Examples include 枕头 zhěntou (“pillow”), 馒头 mántou (“steamed bun”), and 骨头 gǔtou (“bone”).

Less commonly, 头 can affix to a verb or adjective, turning them into nouns. For example, adding 头 to the verb 念 niàn (“to think”), you get 念头 niàntou (“idea” or “thought”), while 甜头 tiántou (“sweet taste” or “benefit”) is formed from the adjective 甜 tián (“sweet”) combined with the suffix 头.

儿 – ‘r

According to the dictionary, 儿 is a “non-syllabic diminutive suffix.” Sounds complicated, right? In practice, the 儿 suffix carries no meaning and attaches to a (monosyllabic) noun or verb to form a noun.

It’s used mainly in the northern regions of China (such as Beijing), where a car is a 车儿 chē’r, a stick is a 棍儿 gun’r, and a painting is a 画儿 huà’r.

When 儿 is a noun—and not a suffix—it’s pronounced ér and means “son” or “child.” You’ll find it in such words as 儿子 érzi (“son”), 女儿 nǚ’ér (“daughter”), and 婴儿 yīng’ér (“baby.”)

边 – Bian

边 biān (first tone) usually means “side,” as in 她坐在我旁边 Tā zuò zài wǒ pángbiān (“She sat by my side”).

When pronounced with a neutral tone, 边 bian attaches to nouns of a locality to indicate a direction or side, as in 左边 zuǒbian (“left”), 右边 yòubian (“right”), or 南边 nánbian (“south”).

们 – Men

Regarding plurals, the Chinese language tends to be pretty straightforward. Since Chinese nouns can represent singular and plural nouns, there’s no direct equivalent to the English plural suffix “-s.” It also means that there are no irregular plurals in Chinese.

Although most plurals do not require suffixes, a Chinese character is commonly used in certain regular and irregular plurals. Therefore, when searching for a way to translate the English plural suffix or irregular plurals, you’ll frequently find 们 used in combination with other characters.

As a morpheme, 们 men has no meaning except when combined with another word. It’s mainly used to form Chinese pronouns, such as 我们 wǒmen (“we,” “us”), 你们 nǐmen (“you” [plural]), and 他们 tāmen (“they”).

Aside from the standard pronouns, you can use 们 to pluralize specific human nouns. 们 stands in for the English suffixes “-s” and “-es,” as well as forming irregular plurals such as “men,” “women,” and “children.” Use 们 to turn 朋友 péngyou (“friend”) into 朋友们 péngyoumen (“friends”), 孩子 (“child”) into 孩子们 háizimen (“children”), and 同志 tóngzhì into 同志们tóngzhìmen (“comrades.”)

Remember that the suffixes in the Chinese examples are not required. Although 们 stands for the English plural suffix, in some cases, you cannot use it with numbers. 我们有三个孩子们 Wǒmen yǒu sān gè háizimen (“We have three children”), therefore, is grammatically incorrect. Instead, use 们 when you want to speak about a general group, as in 孩子们在做作业 Háizimen zài zuò zuòyè (“The children are doing their homework.”)

From time to time, you’ll hear people use 们 to form the plurals of non-human animals or other animate nouns, replacing the English plural suffix “-s” in words like “ducks,” “pigs,” and “bears” and forming the Chinese for irregular plurals such as “sheep,” “geese,” and “mice.”

It’s not standard usage, but you’ll often see 们 used with animate nouns in children’s stories and fairy tales where animals are personified. For example, in the Chinese translation of Richard Adams’s classic novel Watership Down—known, somewhat hilariously, as 兔子共和国 Tùzi gònghéguó (“Rabbit Republic”) in Chinese—the rabbits are referred to as 兔子们 tùzimen. Chapter Five opens with the line:

兔子们离开原野,走入一片树林时,已经快到月落时分了。

Tùzimen líkāi yuányě, zǒu rù yīpiàn shùlín shí, yǐjīng kuài dào yuè luò shífēn le.

It was getting on toward moonset when they [the rabbits] left the fields and entered the wood.

学 – Xué

When used as a suffix, 学 stands for “-ology” or “-istry” in English. In Mandarin, you frequently translate terms for academic disciplines by adding 学 to the subject of study.

In Chinese, 生物学 shēngwùxué (“biology”) is the study of 生物 shēngwù (“living things”), 数学 shùxué is the study of 数字 shūzì (“numbers”), and 神学 shénxué (“theology”) is the study of 神 shén (“god,” “spirit,” “divinity”).

主义 – Zhǔyì

You can use 主义 when referring to various ideologies and doctrines of thought. In Mandarin, you frequently translate the English phrases for various ideologies marked with the “-ism” suffix by adding the characters 主 zhǔ and 义 yì.

Some examples include 社会主义 shèhuìzhǔyì (“socialism”), 女性主义 nǚxìngzhǔyì (“feminism”), and 共产主义 gòngchǎnzhǔyì (“communism”).

的 – De

What’s the Chinese particle of possession doing here, you might ask, in our list of Chinese suffixes? Well, although it’s not technically a suffix, 的 does have the ability to describe properties by marking something as “possessing” a particular characteristic.

For that reason, you can frequently translate the English suffixes “-ific” and “-atic” using 的, in terms like 了不起的 liǎobuqǐ de (“terrific”), 系统的 xìtǒng de (“systematic”), and 自动的 zìdòng de (“automatic”).

家 – Jiā

As a stand-alone noun, the primary meaning of 家 jiā is “home” or “family.”

家 is also one of the nominal suffixes used to describe a specialist in a particular field, such as a 科学家 kēxuéjiā (“scientist”) or 作家 zuòjiā (“writer”).

者 – Zhě

The versatile Chinese suffix 者 is affixed to many adjectives, verbs, and noun phrases. It’s another one of the suffixes used to describe jobs and professions.

者 is most commonly attached to verbs to indicate those engaged in a particular activity and is used in many generic job titles. For example, translators in Chinese are known as 译者 yìzhě, journalists are called 记者 jìzhě, and volunteers are 自愿者 zìyuànzhě.

When attached to an adjective, 者 describes properties or characteristics of a person or group, such as 拼着 pínzhě (“the poor”), 伤者 shāngzhě (“the wounded”), or 死者 sǐzhě (“the dead”).

Finally, you can affix 者 to noun phrases ending with 注意 zhǔyì (-ism) to describe someone who adheres to a particular belief or doctrine, such as a 马克思主义者 mǎkèsīzhǔyìzhě (“Marxist”), a 环境保护这 huánjìng bǎohùzhě (“environmentalist”), or a 素食主义者 sùshízhǔyìzhě (“vegetarian”).

员 – Yuán

You use 员 to describe people who are engaged in an activity or members of a group or organization in a phrase like 社会的一员 shèhuì de yī yuán (“a member of society.”)

You can also use 员 yuán as a nominal suffix to form new nouns, most commonly relating to group members or team players. Common examples include 会员 huìyuán (“member”), 队员 duìyuán (“teammate”), and 党员 dǎngyuán (“party member”).

Some nouns relating to jobs and professions are also formed using the 员 suffix, including 演员 yǎnyuán (“actor”), 球员 qiúyuán (“player” – on a sports team), and 教员 jiàoyuán (“instructor”).

性 – Xìng

The primary meaning of 性 is “nature” or “quality,” When used as a suffix, 性 functions like the English suffixes “-ness,” “-ity,” or “-ability.” This versatile suffix converts adjectives into nouns and transforms nouns into adjectives. Let’s begin by learning how to transmute an adjective into a noun:

- 可能 (“possible”) + 性 = 可能性 kěnéngxìng (“possibility”)

- 可靠 (“reliable”) + 性 = 可靠性 kěkàoxìng (“reliability”)

- 实用 (“useful”) + 性 = 实用性 shíyòngxìng (“utility,” “usability”)

- 硬 (“hard”) + 性 = 硬性 yìngxìng (“hardness”)

- 毒 (“poisonous”) + 性 = 毒性 dúxìng (“toxicity,” “poisonousness”)

Working in reverse, let’s learn how to wave our alchemical wand over a noun and transform it into an adjective. In this case, 性 will usually stand for the English suffix “-al:”

- 教育 (“education”) + 性 = 教育性 jiàoyùxìng (“educational”)

- 季节 (“season”) + 性 = 结节性 jìjiéxìng (“seasonal”)

- 技术 (“technology”) + 性 = 技术性 jìshùxìng (“technological”)

The magic 性 has one more trick: turning verbs into nouns that describe qualities. Examples include:

- 开放 (“to open”) + 性 = 开放性 kāifàngxìng (“openness”)

- 创造 (“to create”) + 性 = 创造性 chuàngzàoxìng (“creativity”)

- 传染 (“to infect”) + 性 = 传染性 chuánrǎnzìng (“infectiousness”)

度 – Dù

度 means “degree” or “extent” and is found in Chinese words such as 温度 wēndù (“temperature”), 角度 jiǎodù (“angle”), and 幅度 fúdù (“range”).

While a Mandarin Chinese dictionary may not specify 度 as one of the suffixes, it often acts like one. For example, use 度 to transform an adjective into a noun, forming nouns such as 力度 lìdù (“strength”), 高度 gāodù (“height”), or 速度 sùdù (“speed”).

化 – Huà

The original meaning of 化 is “to change” or “to transform.” As a suffix, 化 refers to the process of doing something and converts adjectives and nouns into verbs. You can think of it as replacing the English suffixes “-ize,” “-ify,” and “-en.”

If you need to make something a little more [noun], or a bit more [adjective], the suffix 化 might be just what you’re looking for:

- 深化 shēnhuà (“deepen”)

- 恶化 èhuà (“worsen”)

- 简化 jiǎnhuà (“simplify”)

- 净化 jìnghuà (“purify”)

- 氧化 yǎnghuà (“oxidize”)

- 现代化 xiàndàihuà (“modernize”)

地 – De

地 is an adverb marker in Mandarin and the simplest way to create Chinese adverbs from adjectives.

Adding 地 onto the end converts adjectives into adverbs, just like the adverb marker “-ly” in English. Examples include 耐心地 nàixīn de (“patiently”), 开心地 kāixīn de (“happily”), and 伤心地 shāngxīn de (“sadly”).

Usually, you’ll need to double-up monosyllabic adjectives before adding the adverb marker to create adverbs like 慢慢地 mànmàn de (“slowly”) and 悄悄地 qiāoqiāo de (“quietly”).

然 – Rán

然 is not nearly as common as 地, but it also functions as an adverb marker in Mandarin and is used to form both adverbs and adjectives. The most common examples are 忽然 hūrán and 突然 tūrán, both of which mean “suddenly,” 居然 jūrán, meaning “unexpectedly,” and 显然 xiǎnrán, meaning “obvious” or “obviously.”

You’ll more often encounter 然 rán as a morpheme in many Chinese conjunctions, such as 虽然 suīrán (“although”), 既然 jìrán (“since,” “as”), and 不然 bùrán (“otherwise”).

兮兮 – Xīxī

A fun and colloquial phrase, 兮兮 has no meaning in itself, but you can use it to exaggerate certain adjectives, including 脏 zāng (“dirty”), 神秘 shénmì (“mysterious”), and 可怜 kělián (“pitiful”).

In China, it’s used to poke fun, and you’ll also encounter it in fiction and movies, in lines like 可这些脏兮兮的工作总要有人做的 Kě zhèxiē zāngxīxī de gōngzuò zǒngyào yǒurén zuò de (“It’s a dirty job, but someone’s gotta do it.”)

You’ll also hear Chinese people say 神经兮兮 shénjīng-xīxī (“nervy,” “neurotic”), although 神经 (“nerve”) is technically a noun:

要我说,你的男友有点儿神经兮兮的。

Yào wǒ shuō, nǐ de nányǒu yǒudiǎn’r shénjīngxīxī de.

If you ask me, your boyfriend seems kind of a nutjob.

If you’ve read this far, you’ve not only learned some useful new vocabulary but increased your understanding of prefixes and suffixes in Mandarin and their equivalent terms in English. Hopefully, you’ll have more of a clue about separating your characters from your characteristics, turning numbers into ordinals, and differentiating the doctrines and qualities from the various ideologies. You’ll be able to express your -ologies, -ists, and -isms, and understand the difference between “science,” “scientist,” and “scientism” in Chinese.