Mandarin Tone Pairs – Tones Come Better in Pairs

Tone Pairs & Tone Pairs Anchors

Last week, we talked about the Mandarin tones in general, this week we’d like to get a bit more specific and talk about Mandarin tone pairs.

Teachers tend to teach tones in isolation, and hey, it is not wrong to start to understand Mandarin tones by studying that way. Doesn’t make sense to skip to more advanced tone techniques before understanding the basics, but consider that you always want to be considering the frequency at every part of your Chinese learning journey. Frequency, you guys. Frequency. “Mandarin Tone pairs” are the most frequent of all. Why?

First, you need to understand the basics of Chinese words. There are a few possibilities for how many characters are in what is considered a word:

- One Character Words – e.g., 水 shuǐ – water, 吃 chī – to eat

- Two Characters Words – e.g., 中国 zhōngguó – China, 反省 fánxǐng – to reflect (e.g., on oneself)

- Three Characters Words – e.g., 怎么样 zěnmeyàng – how about it?

- *Four Characters Words – e.g., 顺其自然 shùnqízìrán – to let nature take its course

- *Four+ Characters Words – e.g., 眼不见心不烦 – yǎnbujiànxīnbufán- Out of sight, out of mind

*Note: With the 4 or 4+ “words,” many would argue they aren’t words, but rather more complex idioms or sayings. Chinese is so effective with expressing incredibly large amounts of meaning with only four characters, so they’re almost like words on steroids.

The next question is, amongst these possibilities, which one constitutes the highest ratio of everyday Chinese words? Is the suspense killing you? It shouldn’t because it is an absolute blowout. Two-character words are by far the most common in Mandarin. There was a time in history when the majority of words in Chinese were one character, but as the language evolved and became more complicated to help people better articulate their more profound understanding of the world around them, one-character words weren’t cutting it anymore.

Mandarin Tone “Pairs”

Considering that the majority of frequently used Chinese words are two characters, the time spent focusing on sets of two tones together (tone pairs) should constitute the majority of your focus when thinking about tones. Sure, you needed to know the individual tones, but only so you can take it to this next step.

Let’s do a little bit of math to figure out where your aim should be. There are five tones in Chinese, but the 5th tone only appears after other tones. There aren’t any Mandarin tone pairs that start with the 5th tone (e.g., the 5th tone followed by a 2nd tone). The other four tones can be used either first or second. This means you’d have four tones x 4 tones=16 possible tone combinations, then add another four possible tone pairs since the 5th tone can go after tones one through four bringing you to 20, BUT WAIT!

In Chinese, it is actually not possible to have two 3rd tones in a row (more on that later), so when two characters that are naturally 3rd tone are combined (e.g. 你 nǐ – ‘you’ & 好 hǎo – ‘good’), the first of the two characters changes to 2nd tone (e.g. 你好 níhǎo – ‘hello’). This means that there are only 19 possible tone pairs because the 2nd tone – 3rd tone exists in two situations, when it happens naturally and when two 3rd tones are next to each other.

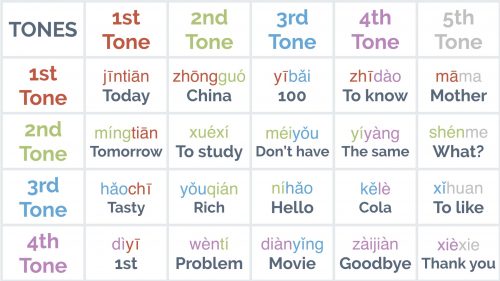

Let’s take a look at this chart to get a better view:

The above tone pair anchor examples are widespread words. It is when your vocabulary grows that you start to get tones. When you are first learning them, it’s all a bit muddy and confusing. There is no context. However, when you’ve mastered these 19 tones pairs, you have SO MANY opportunities to catch them when listening to or reading Chinese. Most sentences could be conceptualized from a pronunciation perspective as a set of tone pairs, as most words are two characters.

Tone Pair Anchors

Now that you know what tone pairs are, you should pick words to serve as tone pair “anchors.” Each word should be high-frequency, so you’ll say it often. It should also be a word that you like. Perhaps because of how it sounds. Maybe because you like the meaning. Whatever you choose, make it feel like it’s your anchor word. Create a relationship with the word. These 19 words will follow you through the whole process of learning tone pairs.

A great example of this would be the word for “Thank You” – 谢谢 xièxie. This is probably the best tone pair anchor for the 4th tone – 5th tone you could ask for because you are going to say it every day. Your likelihood of practicing it naturally without forcing yourself is super high. We’re all about putting your head down and practicing, but we’re also all about increasing your chances of success through simple hacks.

“You don’t have to run tomorrow morning, you just have to standing outside with your gym shorts and sneakers on” –Khatzumoto

So how will it work? Well, imagine that you’ve said 谢谢 xièxie accurately hundreds of times. Later you are going to learn another word with the same Mandarin tone pair. Perhaps it will be the word 态度 tàidu, which means “attitude.” When you go to learn that word, while it is true that the consonant & vowel sounds are entirely different than 谢谢, the pitch is the same. Let’s review:

- Realize that tone pairs are more critical than tones in isolation.

- Listen to and be able to mimic the 19 possible tone pairs

- For each tone pair, pick a high-frequency word that you like to be your “tone pair anchor.”

- When learning a new word, look at which tone pair it is, call-back to your tone pair anchor word so that you can at least get the pitch correct

- Do this until all tone pairs become second nature (this will only get easier as time goes on)

We’ve made an Anki Deck shared via Dropbox, ten cards representing each tone pair. Every word on the list is high frequency, so any of them would be perfectly fine to choose as your “tone pair anchor.”

Ever heard of Anki? Here’s some introductory videos we made on how to use it: Mandarin Blueprint’s Anki Playlist on YouTube

On “Tone Change Rules”

We’ll have blog posts in the future (now available) about how all this works but bear in mind for now that sometimes tones change in Chinese to make the sentences flow more evenly and sound more relaxed.

Rule #1 – “一 yī – one”. The second most common character in the language.

Rule #2 – “不 bù – (negation)”. The word is used when you want to negate something (e.g., want 要 vs. don’t want 不要).

Rule #3 – 3rd tone. You can’t have two 3rd tones in a row (and thus can’t have a 3rd-3rd tone pair).

We’re sure you can see how these three rules will come up all the time. Naturally, that means they are worthy of your attention.

Certified Tangent

(because ideas sometimes come up when writing :D)

Tone change rules are one of the best ways to understand when you should focus your rational mind on some principled understanding of the language you are learning vs. when you should let your intuitive thinking subconsciously make the acquisition. Three-tone change rules happen all the time (mentioned above). After that, there are countless tone change rules that occur naturally in speech sporadically and without much frequency.

It is worth studying a principle if your opportunities to notice it are all around you. It is not worth it (especially with language) if it doesn’t come up all that often. Learning rules for more obscure tone change patterns in the early stages is like trying to understand how to build a window on the 50th story building before you’ve figured out how the foundation keeps the whole building up. TANGENT COMPLETE.

Summary & Suggestions On Tone Pairs

- When you use tone pairs, you are speaking “real” Chinese

- As mentioned above, you will use more two-character words than one character words when speaking. Chinese is packed with two-character words.

- Get exposed to tone changes right away

- Learn tone pairs & tone changes based on how Chinese people speak, not based on practicing them in isolation. More subtle tone changes will come naturally after your foundation is already built up. (BTW this is exactly how we teach pronunciation in our acclaimed Pronunciation Mastery Course)

- Tone pairs expose weaknesses

- Not all tone pairs are equally challenging to articulate. You may discover that a particular tone pair gives you more trouble than others. Just as people who are at the top of their field practice on their weaknesses more than their strengths, so should you find your tone pair weaknesses and put extra energy into them.

Dealing with tones in terms of “pairs” is the best level at which to focus on them in the beginning. You save yourself a lot of time, in the long run, this way. Chinese is full of this type of thing. The key is not to fool yourself about it. For example, one response you might have in learning about tone pairs is “Geez, I thought I had to learn five tones, now I’m finding out I need to master 19 tone pairs?! That’s too much!”. Another response might be: “Oh good, I found another key to long-term success, and this will give me an edge moving forward.” Which way do you want to look at it?

保重,

Luke & Phil