Chinese Letter E – Comprehensive Guide

Chinese Letter E Part 1 – Such a Hungry Letter 饿 è

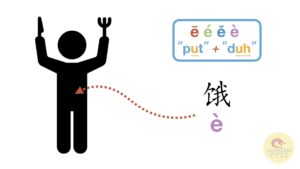

Chinese letter E gives everyone trouble, us included. Good news though, it is only ever pronounced this way when it’s a simple final. Even better than that, it’s only pronounced the way Luke describes in the video when it has tones 1-4! At least when things are difficult you can be grateful it isn’t ubiquitous across the entire language. It is a diphthong that combines the vowel sounds of “put” with the vowel sounds of “duh”. You DO NOT move your lips when saying it.

Ew, Gross! I’m Hungry.

Interestingly, by itself, this sound is very close to the disgusting sound in English. When you look at a gross thing, you’ll often say “ew!” or another similar onomatope. Seeing as 饿 è means “hungry” in Chinese, well, just shows that the ‘disgusted’ sound is not universal. (tangent…did you know that the disgusted facial expression IS universal across cultures? The more you know.)

Watch Out

Foreigners often forget to fully articulate Simple Final E when there is an initial in front of it. Sure, they learn it correctly when it is just “饿 è”, but what about 歌 gē (song), 和 hé (and) or 渴 kě (thirsty)? You still say it in FULL as Luke describes in the video. Remember, this is only true when it is attached to tones 1-4, NOT 5th.

Pay More

Learning Chinese made us think more about which verbs are used for which actions. Sometimes it has made us surprised at certain verbs that are used in English. Consider that we say ‘pay’ attention. Profound. When I think about it, nothing is more valuable to a person and to other people than your attention, so sure, you are “paying” it. PAY MORE when looking at Simple Final E.

Chinese Letter E Part 2 – The Dreaded 了 le

Pronunciation

In the previous post in this series, we talked about how Simple Final E is a diphthong. The exception, however, is when it has a 5th tone, like 了 le. When combined with tones 1-4, it is a combo of the vowel sounds in “put” + “duh”. When combined with the 5th tone, it’s just that “put” vowel sound by itself. Easy peasy.

Grammar

When Phil was in Beijing and just starting to learn Chinese, he asked his bandmate, Daniel, about 了. Daniel is from Barbados and at the time had been studying Chinese for a few years. He struggled to find the answer because every time he thought he knew what to say about 了 an exception came to mind. In the end, Daniel just shrugged and said “了 is f#&@ed up”. We feel his pain.

In fact, Chinese scholars are still debating about some of the uses of this particular grammatical particle. Last year a professor at Sichuan university asked Phil to proofread the English abstract on an academic paper. Unsurprisingly, it was a five-page paper on a rare use of 了. Once again, we found evidence that it is difficult to find a catch-all explanation for this particular simple character.

You might be wondering, why would a grammatical particle be so complicated? We speculate that the reason that such a particle evolved is that the Chinese don’t have words that change form. We’ve mentioned in a past article on Chinese letter a that grammar has three functions. It can change word order, add words or change their form. Chinese doesn’t have that third one. As a result, the idea of “past tense” isn’t really there.

Is 了 the Past Tense Marker?

NO!!!! In English, we change the form of words (most often by adding “-ed”, but not always) to indicate past tense. “Want” changes to “wanted”, “go” changes to “gone” or “went”. “Run” changes to “ran”. You get the idea. Chinese never changes the form of words, so how does it deal with past, present, and future?

What if we didn’t think so much in terms of past, present & future, but rather in changes? After all, we tend to talk about the past or future in terms of the change that has happened or will happen from the present. This isn’t the only way to conceptualize these temporal distinctions, but bear with us, this all comes back to 了.

So How Should We Think of 了?

The best way to think of 了 in the early days is as a change indicator. Nested within that idea is the completion of actions, a sub-set of ‘change’. Every time you see 了 in a sentence, ask yourself “Where is the change?”. You’ll thank us later.

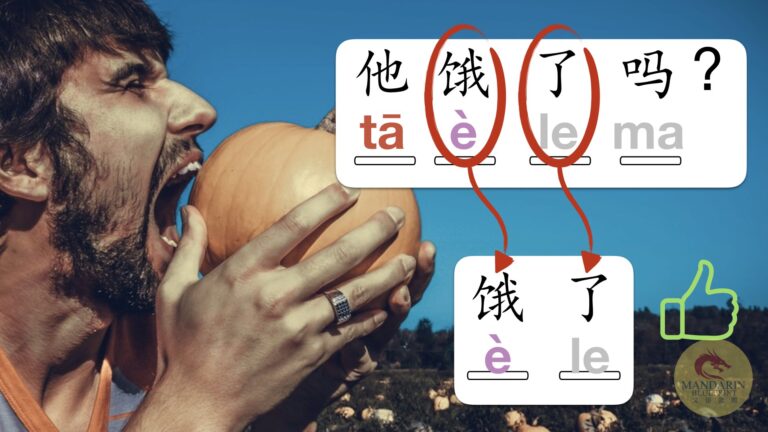

他饿了 tā è le was mentioned in the video above. Why add 了? Well, it’s because earlier you weren’t hungry, and now you are. There is a change that has taken place. In this context, it is very similar to when we put “now” at the end of a sentence in English. “He’s hungry” is just a statement. “He’s hungry now” indicates the change. You can see what 了 would be used in relation to hunger as it is constantly in a state of flux.

The sentence 他饿了 also does a good job of indicating that the use of 了 is A) Not necessarily used to indicate past tense (he’s currently hungry) and B) Isn’t always used as the completion of an action.

The completion of an action side of things is the easiest to understand conceptually. Let’s use the most overused Chinese example sentence to illustrate this:

A: “你吃饭了吗?nǐ chī fàn le ma? Did you eat?”

B” “吃了” chīle “Yes, I ate”

The action of eating (吃) has been completed (了). Completed actions indicate change, so as stated above, they are nested within the rule of 了 being a change indicator. BTW, you may have noticed that the translation included “Yes”.

**CAVEAT FOR NITPICKERS**: Some of you reading this are likely advanced Chinese students who are aware that certain usages of 了 may not be conceptualized as being in the realm of “change”. First of all, what’s up? Would love to chat with you sometime about how you learned Chinese. Second of all, yes, we are aware of that and are attempting to give a beginner a conceptual framework for getting starting with 了. 希望你能谅解 :).

Paying Attention > Thinking

As with any article that discusses a concept like this, the goal is NOT NOT NOT to make you over-think. We want you to notice. Your adult brain is so much better at noticing than a child’s brain. This is why, with the right guidance, adults can learn the language faster than children. (BTW Gabriel Wyner of Fluent Forever does a great job of dispelling that “children are better at language learning” myth in his Ted Talk). There are countless opportunities to notice 了 in sentences. See a sentence or hear a sentence with 了?Ask yourself where is the change. Try your best NOT to let this rule become something that makes you over-think while speaking. Input is always the first step to fluency. When you see 了 enough times through INPUT, your OUTPUT of it will follow naturally and without the need for over-thinking.

你明白*了*吗?

Chinese Letter E Part 3 – 的 The Most Common Character in Chinese

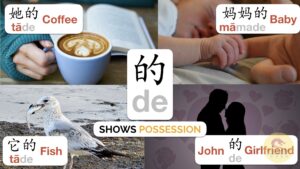

Learning Mandarin makes you realize just how many things BELONG to other things. That’s the main usage of 的 in Mandarin.

Pronunciation

Just like 了 le above, 的 de is a Simple Final E that has the 5th tone, so it’s super easy to say. The “d” sound is included in the “tougher” initials category, but we’ll focus on that in a future post. Seeing as this is the most common character in the whole language, you’ll get this down in no time.

Grammar

Simple Possession

Seriously not difficult, so we won’t harp on it for too long. The simplest form is basic possession of something, and so let’s use his, her’s, your’s & mine as examples:

他的车 tāde chē “His car”

她的东西 tāde dōngxi + “Her stuff”

你的猫 nǐde māo “Your cat”

我的电脑 wǒde diànnǎo “My computer”

Anything can go after the “Pronoun + 的” combo to indicate possession. Just like English, what is being possessed can be concrete or abstract (i.e. his car vs. his idea)

Slightly More Advanced (Not Very)

Things can also “belong” to non-humans, and you’ll also use 的 in these cases. Examples:

电脑的硬盘 diànnǎo de yìngpán – the computer’s hard drive- The hard drive “belongs” to the computer.

成都的环球中心 chéngdū de huánqiú zhōngxīn – Chengdu’s ‘Global Center’. The ‘Global Center’ “belongs” to Chengdu. (BTW, if you haven’t heard of the Global Center, check it out, it’s the largest free-standing building in the world by surface area).

There are more things to consider when it comes to 的, but simple possession is all that’s necessary for now. Because 的 is the most common character in the whole language, your opportunities to notice it will be overwhelmingly large. You got this.

你们 *的* 好朋友们,

Simple Final E Part 3 渴,可乐,喝

The final video on Simple Final E gives a chance to consider a few interesting new concepts. The importance of tones is huge here.

Pronunciation

可乐 kělè is the Chinese loanword for “Cola”. Note that both syllables have a tone, so they are fully articulated diphthongs. It is also our first 3rd Tone – 4th Tone Tone Pair. We consider this to be one of the more difficult tone pairs, so give it some extra focus.

渴了 kěle “thirsty”, on the other hand, has a syllable (了) that doesn’t have tones 1-4. That means it is NOT a fully articulated diphthong. Comparing 渴了 to 可乐 is all about the second syllable, as the first is exactly the same. The biggest mistake we’ve noticed our students making when comparing these two is that they try too hard when saying 了. It is the 5th tone & not a diphthong, so it’s quite short. Because it comes after a 3rd tone, it is also high in pitch. Don’t overdo it!

喝 hē “to drink” introduced the “tougher” initial “h”. Tougher initials are defined as being similar to English, but not exactly the same. In this case, “h” is considerably harsher & raspy, much like how you say “chutzpah” in Hebrew or how Scottish people say “loch”. We’ve noted that Chinese woman tends to say this a bit less intense than Chinese men. Even still, it is not quite so light as it is in English.

Vocab

Take a note of the characters 喝 hē & 渴 kě. They are a great teaser for what you’ll learn when getting into Chinese characters. Note that the right side is the same for both. That said represents a phonetic clue. Many people think Chinese is not phonetic at all, but it would be more accurate to say that it is LESS phonetic than English. After you learn character components, you’ll see there are phonetic clues all across the language. They aren’t perfectly objective though, as evidenced by the fact that “hē” & “kě” aren’t exactly the same. They are, however, in the same pronunciation family as they both have the Chinese letter E.

Now let’s look at the left side of 喝 & 渴, 口 & 氵. First of all, note that “to drink” and “thirsty” are conceptually in the same realm. When you are “thirsty”, you need water. Wouldn’t you know it, the 氵in 渴 is the Chinese component representing water! Clever. When you finally get to “drink” some water, you put it into your “mouth”. Whoa whoa, that’s crazy look at that 口 on the left of 喝 “to drink”. It means “mouth” (big surprise, just look at it!). Don’t be intimidated by Chinese characters, look at them with fascination. You’ll learn constantly from them. Stay focused on pronunciation for now, but start mentally preparing yourself to really delve deep into 汉字 hànzì ‘Chinese characters’.

Thirsty? Drink Some Cola!

As you continue through these videos and posts, remember that you’re well on your way to mastering everything about Chinese pronunciation. It isn’t only achievable, it’s easier than it’s ever been. Yes, focusing so much on pronunciation, in the beginning, might feel frustrating sometimes, but the dividends it will pay of in the future are simply phenomenal.

Thirstily Yours,

Luke & Phil

The video and written content is part of Mandarin Blueprint’s Pronunciation Mastery Video Curriculum.