Tone Change Rules In Mandarin Chinese

OK OK, so we already know about Mandarin tones, but there are also tone changes. “Geez, Luke & Phil” you might be thinking, “First it’s tones, then it’s tone pairs, now this?! Why don’t I just switch my learning focus to rocket science or brain surgery? Clearly much easier than Mandarin Chinese!”

Alright alright, calm down hypothetical hyperbolic protestor, we’ve got you. Besides, everything seems harder than it is when you first look at it.

Three questions naturally arise when considering what to do about these pesky tone changes:

- Why do Chinese tone changes exist?

- How do Chinese tone changes function technically?

- When should I learn the rules of Chinese tone changes & when to learn organically?

Lovely, now that we’ve figured out the right questions to ask, answers are in order. As it turns out, we’ve got a few ;).

Why Do Chinese Tone Changes Exist?

Swift & Smooth > Clunky & Slow

Another word for tone changes is tone “sandhi”. The word “sandhi” derives from Sanskrit, and it refers to a “wide variety of sound changes that occur at morpheme or word boundaries.” Sandhi exists situationally in words or between words in most languages. For example, if you say the word “govern”, you’ll enunciate the “n”. How about “government”? Whoa, where did the “n” go? It’s still there in spelling, but guess what? The rules of English phonetics don’t account for the fact that saying the “n” sound followed by the “m” sounds just downright silly. Trying to enunciate both would be clunky & slow, but we humans like to be swift & smooth when communicating. Hence the existence of “sandhi” for words.

Yeah yeah, “word” sandhi, but what about tone sandhi?

The fundamental difference between “tonal” languages and non-“tonal” languages aren’t actually the existence of tones. English obviously has tones (“I can’t believe it” vs “I can’t believe it”). The real difference exists at which level of the language tones are most frequently used. Tonal languages like Chinese use tone of voice most frequently at the level of the word. Non-tonal languages like English use tone of voice most frequently at the level of the sentence. This introduces a problem for tonal languages.

You see, when Chinese people decide to say a series of words in order to string together a thought, they aren’t thinking about whether the tones of the words they are using fit together nicely. They’re thinking about the words they want to say. With 19 different 2-character word tone pairs, 1-character words, 4-character idioms, etc., possible tone combinations are virtually infinite.

So? Well, maybe the words you choose to string your thought together end up creating five 4th tones in a row. It’s possible! Remember how 4th tone sounds? All assertive like that? Well five of them in a row would sound weird, hard to say, clunky, and darn right aggressive! 怎么办?Tone sandhi to the rescue!

How Do Chinese Tone Changes Function Technically?

Unlike word-based “sandhi”, Chinese tone changes (tone sandhi) don’t change the way letters are said. Chinese tone changes take a tone that was previously 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th tone and change it to a different tone (including 5th tone). Let’s use one of the most common Chinese tone changes to illustrate, the second most common character “一 yī – one”:

Chinese tone changes 一 (yī)

一 yī is the second most common character in Chinese and is likely the first character you learned or will learn. It simply is the number 1. That said though, consider that the concept of one can also imply “unity” (“We are all united as one!”) or completeness (“Everything’s back in one piece!). Chinese recognizes this concept quite well, so many times “一” is used in words unrelated to the numeral 1. They make this distinction aurally through a tone change. Here are the rules:

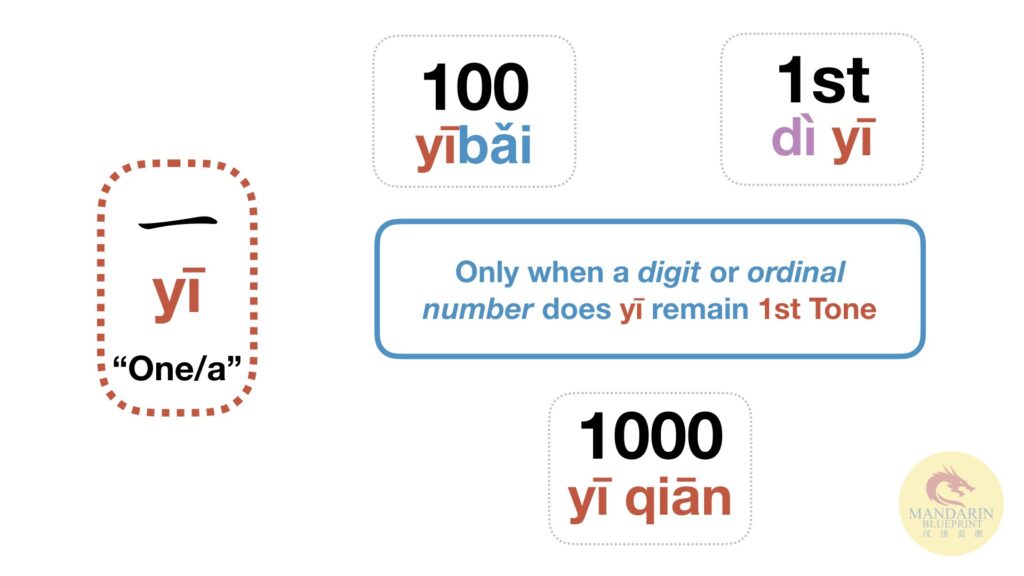

- Only when it’s a numeral or ordinal number is it pronounced as a 1st tone

- 一百 yībǎi – one hundred

- 十一 shíyī – eleven

- 第一 dìyī – 1st

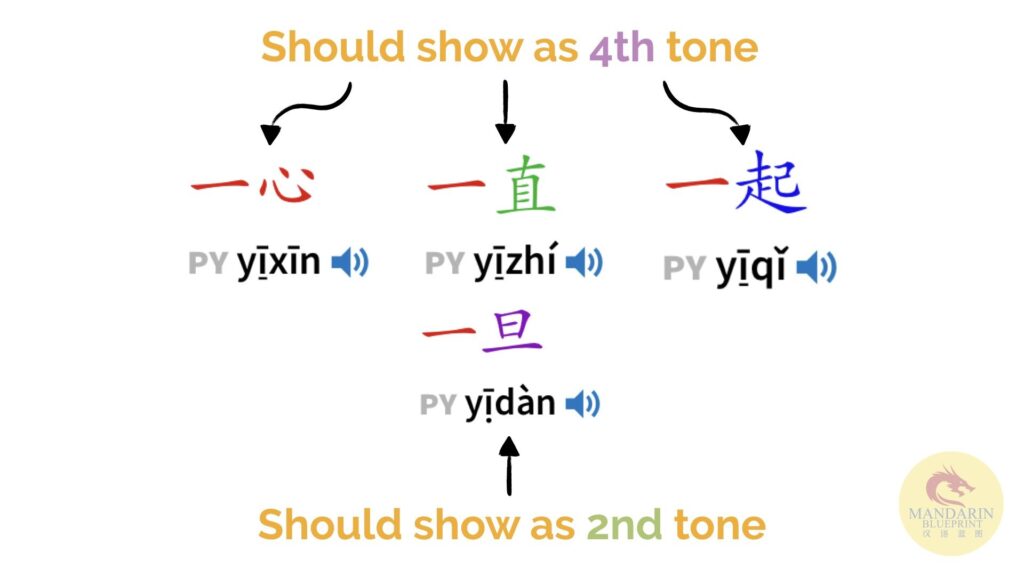

- Before a 1st, 2nd, or 3rd tone, it becomes a 4th tone

- 一般 yìbān – fine, normal, regular

- 一直 yìzhí – continously

- 一起 yìqǐ – together

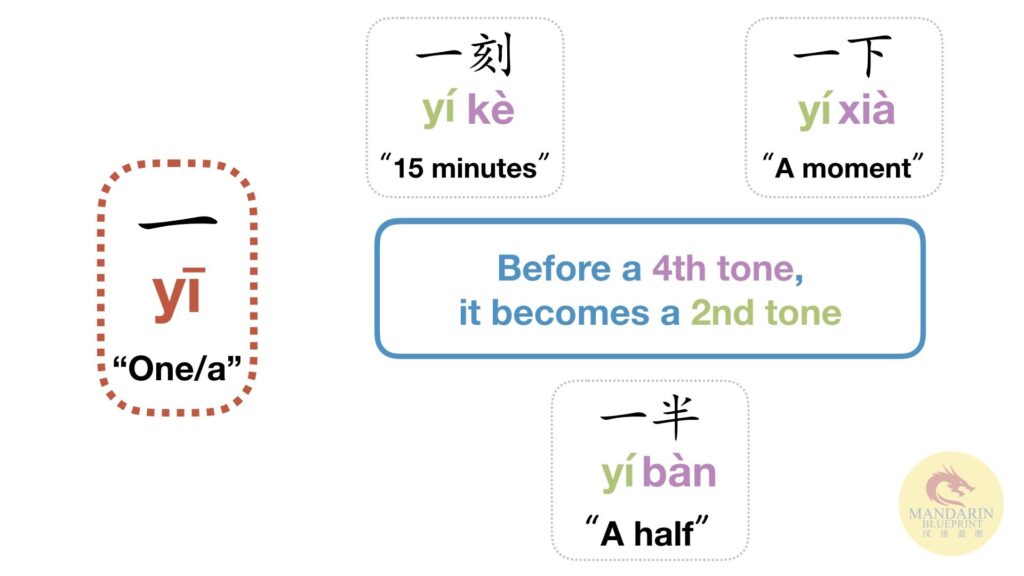

- Before a 4th tone, it becomes a 2nd tone

- 一旦 yídàn – as soon as

- 一定 yídìng – certainly

- 一样 yíyàng – same, the same

These rules exist partly to aurally distinguish between the numeral definition of “一” and the more abstract definitions, but also because it tends to flow better. For example, any 2nd tone – 4th tone combination is really easy to say, whereas 1st tone – 4th tone sounds a bit unnatural. (BTW we did a whole video about the tone pair combinations we find the be the most difficult, check it out).

NOTE: Pleco (incredible as it is as a study tool) does NOT make note of any of these important tone changes. Depending on which version you have, it might just put a little dot under the pinyin for “一” (yī), but you may not even be that lucky! It always writes as the first tone, and this is wrong.

When to Learn the Rules of Chinese Tone Changes & When to Learn Organically

Here’s the thing…if you were to really hyper analyze Mandarin, you’d discover that tone changes happen a lot. Learning all of them as rules would be a waste of time, but does that mean don’t ever learn any rules? Well…sometimes. Ah, nuance, my old friend. Above we talked about the Chinese tone change related to “一 yī“, because it is A) easy to understand & B) incredibly common. It is the second most common character in the language after all.

The conclusion we’ve drawn is that “一 yī” is on the “learn the rule” side of the fine line because its just so darn frequent. You can definitely over-learn rules in a language. For example, there is probably a consistent way to say the character 是 shì “is, am, to be” in the context of angrily expressing indignation after someone implies that you are not something that you are. Perhaps you change to a more exaggerated 4th tone.

Person A: “You aren’t a chef!”

Person B: “What?! How dare you, sir! I am! 我是!”

Worth learning this rule? Obviously not. Why? Because this rule is rare, and unlike the rule for 一 yī carries with it an emotional context. We, humans, are absolutely stellar at remembering things when we have a strong emotion tied to it. Learning it organically is actually easier, and that’s great news.

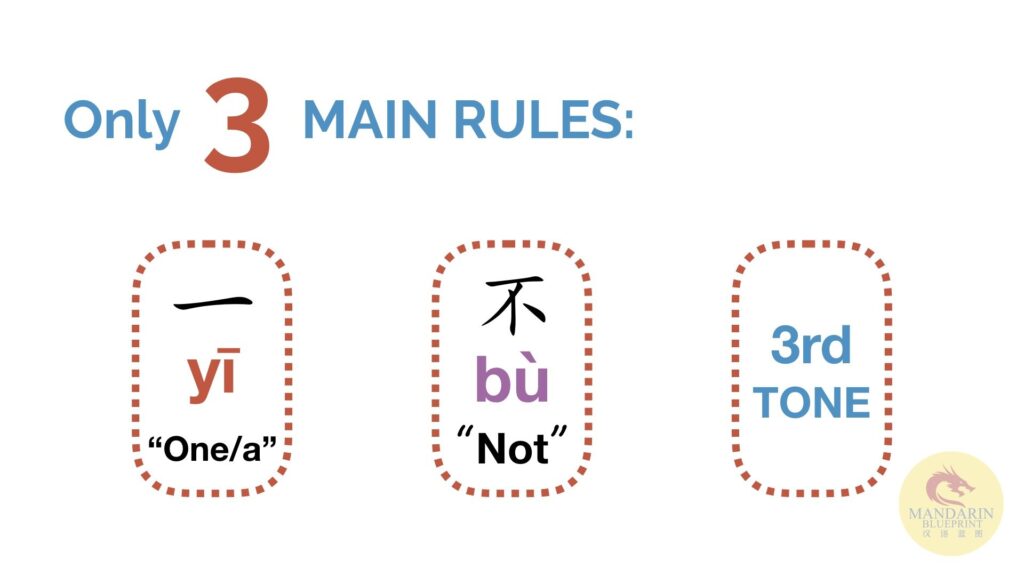

Now that we’ve established a basic understanding of when we should consider learning rules, let’s look at the two remaining rules apart from “一 yī” that happen with incredible frequency. We would submit that these three rules combined occur so frequently that you’d be hard-pressed to find a paragraph of at least five sentences in Chinese that does not have at least one of these tone changes.

Chinese tone changes – 不 (bù)

不 bù is an incredibly frequent Chinese word that is used for basic negation. If you haven’t heard of it before, you will soon. In short, if you want to say “not-[something]” (e.g. not want, not go, etc), the “not” part is 不. There are a few exceptions, but we’ll address those in a future article.

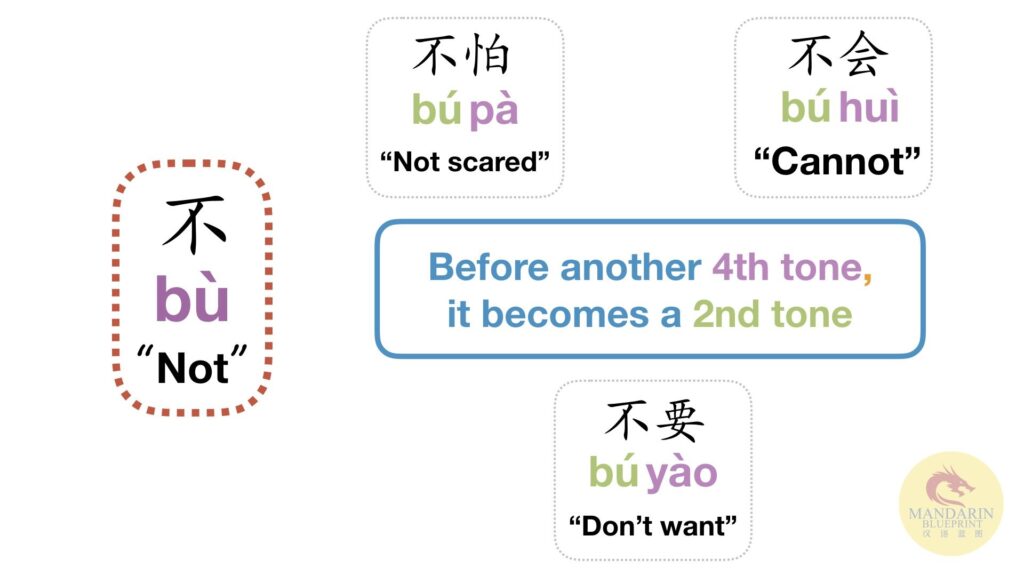

This rule is actually easier than the 一 yī rule because there is only one condition in which 不 bù will change from its standard 4th tone. When before another 4th tone, it becomes the 2nd tone. Once again, the 2nd tone – 4th tone pairing of tones flows very easily.

不要 búyào – don’t want

不错 búcuò – good, not bad!

不是 búshì – not so

不对 búduì – not correct, incorrect

Even if you aren’t familiar with Chinese vocabulary, we’re sure you can imagine just how often you’re likely to say the above four words. If you don’t know the rule, you risk being fooled by your dictionaries. In the same way that in the word “government” we don’t remove the “n” despite it aurally disappearing when written in dictionaries and textbooks “不 bù” is always written as 4th tone. You must notice yourself when it should change to 2nd tone.

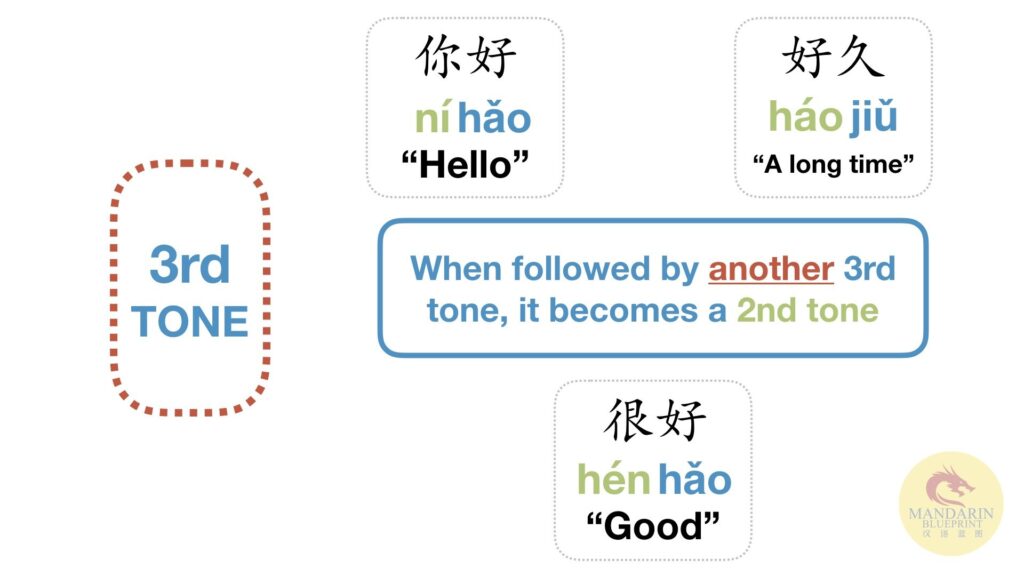

Chinese Tone Changes – 3rd Tone

The final of the most frequent Chinese tone changes is unrelated to vocabulary, but rather just one of the tones in and of itself. 3rd tone, as discussed at length by Luke in this video, is often taught incorrectly. If you say the 3rd tone in context, its length is short, its pitch is low & its quality is a bit croaky. When saying 3rd tone in this manner, it is actually difficult to say more than one in a row while keeping the syllables distinct. Whether consciously or not, spoken Mandarin developed so that there can never be two third tones in a row.

The Rule

When a 3rd tone is followed by another 3rd tone, the first 3rd tone changes to a 2nd tone.

你好 níhǎo – hello

很好 hén hǎo – good

所以 suóyǐ – so

所有 suóyǒu – all

All of these words contain a first character (你,很,所) that is naturally given the 3rd tone. They all change to 2nd tone when said in these words. Once again, Pleco does not show these changes, which means you are responsible for knowing this rule.

What About Multiple 3rd Tones?

Sometimes, while choosing words to string together your thoughts, you may end up with more than two third tones in a row. This only really matters if there are 3 in a row. 5 in a row is rare enough that you don’t need to worry about it. 4 in a row is divisible by 2, so its just 2nd tone – 3rd tone – 2nd tone – 3rd tone (你有所有… ní yǒu suóyǒu…). So how do you deal with three consecutive 3rd tones? There are two options:

Option 1: Change the previous two 3rd tone characters to 2nd tone, leave the final character 3rd tone

我很好 wó hén hǎo – “I’m fine, I’m well”

Option 2: Only change the 2nd of the three characters to 2nd tone

我很好 wǒ hén hǎo – “I’m fine, I’m well”

Either way, the middle character is a 2nd tone and the final character is the 3rd tone. You can choose which you’d like the first of the three to be. We prefer Option 2, but they are both acceptable and frequently said by Mandarin speakers.

NOTE: Even when 3rd tones appear consecutively between words this rule still applies. Take the sentence “他很喜欢你 tā hén xǐhuan nǐ – “He really likes you” for example. 很 & 喜 are both naturally 3rd tones, but 喜 is part of the word 喜欢. In the context of this sentence, 很 is an adverb meaning “very” or “really”. They are separate words, but 很 changes from 3rd to 2nd tone nonetheless.

Don’t Sweat It, Just Notice

These three tone change rules constitute a huge percentage of Chinese tone changes, but remember that there are plenty of other situations where “Tone Sandhi” will present itself. Sure, the main three rules are most important, but keep your eyes and ears open. The chances to notice tone change rules are all around

One last simple tip, see if you notice when tones change from their original tone to 5th tone. 5th tone is short, so sometimes words will change to 5th tone to make the sentence flow better. This “change to 5th tone” observation is usually inconsistent, hence why its more a “tip” than a “rule”. Just look out for it.

As always folks, we’re here to address your questions and challenges on the road to fluency. Mandarin Chinese is only going to become a more important language to know as China becomes more and more prevalent on the world stage. If you have any questions or feedback for us, we’re always happy to hear it, but more importantly please take advantage of our free resources. This blog has new articles every week, our YouTube channel & Facebook page have loads of useful content, and we also have a very useful & easy read eBook “How to Speak Chinese Like a Native” available for free.

保重,

Luke & Phil

PS Our Pronunciation Mastery Video Lesson Course now has the first 49 lessons available! Find out why we’ve been receiving such great feedback about it: Sign Me Up